KUOI Radio, Q-EE, started as one of many amateur radio stations on the University of Idaho campus and evolved into one of two student-owned and operated stations west of the Mississippi. The musical format, always the mainstay of KUOI, changed from the smooth and popular sounds of Nat King Cole in the 1940s to the raw urban revolutionary rap of Public Enemy in 1990. KUOI survived inept student government, funding cuts, FCC rules, state watchdogs and a long line of student station managers who were reactionary at worst and brilliant at best. The news programming changed from homegrown productions to AP wire copy to the radical Pacifica Network. Non-musical production, which in the early days included Shakespearean plays, now features topics like Hippie vs. Car, a call-in show that features topics like women’s secret confessions. The story of KUOI is a story of luck and determination. Despite every obstacle thrown in its way, KUOI has survived.

If there ever was an inauspicious beginning, it was KUOI’s. Three paragraphs and a list of officers on the bottom page in the Argonaut announced the hours and schedule of operation. KUOI began as an engineering project in the attic of the old Electrical Engineering Annex Building, approximately where the parking lot to the present day Home Economics Building is located. Although certain icons can mean different things to different people, if a picture of Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney can be drawn in ones mind, an idea of how KUOI was put together might be formed. With equipment borrowed from the NROTC, the university and other individuals, the Voice of the Vandals throbbed out over the airwaves with the whopping power of two watts.

KUOI was the product of a culture which it (KUOI), along with the rest of mass communication, would help dismantle. The campus was a close-knit fabric of living groups, and individuals were often identified by their living group. The Greeks had the Panhellenic and Intrafraternity Councils and the independents had the Independent Councils. Many off-campus students were returning to married GIs who, for the most part, kept to themselves. It was this camaraderie among the students that gave the station-founders the strength to build and expand KUOI. It was never just one student or a small clique of students that ran the show for themselves, but an all-for-one and one-for-all philosophy that powered students. Orval Hansen recalled that every Monday he would go from living group to living group picking up that weeks musical survey to see which son would be featured on the 5:15 Swing Time show.

This is not to say that there were not some dynamic individuals involved at the beginning. The Godfather of KUOI was Glenn Southworth, an electrical engineering major who would later go on to pioneer stereo recording. Ted Cady, son of the Dean of Engineering, was undoubtedly one of the most energetic characters on campus. It was he that would formalize KUOI on campus. Cady was assisted by Orval Hansen, who would later go on to Washington D.C. as a congressman and own five radio stations, and Sam Butterfield, who would later become head of USAID for Asia. Ambitious as they were, small hurdles would always be on the track for them to leap over.

One hurdle, that in a way epitomizes the era, was the hours that the station could operate. Class attendance in the good old days was not optional. Therefore, at the start, it was difficult to find daytime listeners and impossible to find the manpower to pull it off. There was also a paternalistic rule that said all freshmen had to be in their houses at 6:30 p.m., with quiet hours beginning at 7:30 p.m. KUOI had no choice but to limit the programming to 4-6 p.m. Nevertheless, 13 different programs could be heard during those weekday hours. Weekend programming had yet to arrive.

By the fall semester of 1946, things were on a roll. A constitution for the Radio Club had been adopted, which included a clause indicative of the standards and competition of the 1940s. In order to join the club, a prospective initiate had to do 15 hours of service to the organization and attend each weekly meeting. The service would be to work on any of the seven departments of KUOI: announcing, business administration, technical operating, continuity writing, drama, program scheduling and public relations. Furthermore, if a place on the air was open it meant competitive auditioning for the spot.

Playlists for the campus hit parade were gathered by polling each living group. A sample of the popular songs of the times, in order of popularity is in the following list: To Each His Own, In A Shanty Town. Five Minutes To More, The Girl That I Marry, The House of Blue Lights, Stardust, Ole Buttermilk Sky, Rumors are Flying, Surrender and If You Were My Girl. These are the results, in order of popularity, of the first of many KUOI listener polls. These hits of the day were played every Friday on Campus Hit Parade. A comparison with the national polls found that many songs were the same on both lists and that often songs that were popular on the Hit Parade had been popular weeks or months before on the KUOI lists. Later, KUOI and other college stations would be utilized by the record companies to determine which artists should be promoted. Although the hits favored by Idaho students may not have jived with national polls, the station, as indicated by program names, was not trying to innovate any radical changes in radio formatting who better to spin those crazy platters than Sam Butterfield? Sam took his music seriously so seriously that he had a musical critique column in the Argonaut. Panacea . . . features some terrific vibe work, is what he had to say about a tune by the Thundering Herd. On the Nat King Cole trio he said, just now the big boys of the small groups are those three chocolate gentlemen who comprise the King Cole Trio. . . Theyre very slick and listenable and occasionally produce some fine music.

KUOI had, by its first anniversary, developed into quite the station. It had sports with Jack Culbertson, fashion and style hints with Betty Lou Lamon, Western Jamboree with Norman McChann, home-grown comedy with Charles Owen and last but not least, a new electric sign that flashed KUOI at the studio audience. The second year also saw an expansion to programming through the Intercollegiate Broadcasting Company (IBC). The IBC was a loose-knit coalition of college stations that KUOI joined to become its 50th member. Members could exchange programs and use administrative and technical ideas developed at other campuses. College radio started at Brown University in 1936 and by 1940, 12 more stations were on the air.

Considering the impact of WWII, KUOI was not far behind the rest of the country when it started in 1946. Glenn Southworth, KUOIs founder, became an adviser to the IBC. IBC members pioneered the method of broadcasting used at KUOI in the 1940s and 50s. Rather than broadcasting over the airways from a large central antenna, the signal was sent through the electrical wiring system of the university this was sort of a poor mans cable. The wiring system acted like a giant antenna that produced a signal that could be heard only a few hundred feet from the wire. Most college stations, before the advent of FM, were delegated from the 550 to 700 kilocycle range on the AM band. Although this limited the size of the listening audience to the immediate campus area, it freed the editorial policy greatly. The only blue noses that could be offended were those on campus and since more of the stations operated on a non-profit basis, no advertisers could control editorial content.

Controversial subjects tackled were birth control at Brown, textbook pricing at Brigham Young and radical discrimination at Yale. Even though college radio was non-profit, it could advertise. One of the features offered by the IBC was access to the large national advertisers. Lucky Strike cigarettes sponsored a show on KUOI called Lucky Number. The syndicated shows were distributed on platters these ranged from classical music to original plays.

One script writer was able to sell his work to the large commercial networks but one of his plays about religious persecution was too hot to be handled by the commercial networks, and only was heard on the IBC. KUOI was producing three-act plays that were to be aired on act a night.

The IBC also allowed KUOI to go on a more full-time schedule. KUOI now was on the air from 7 a.m to 9 p.m. Not only that but they got the OK to build an official studio, complete with triple-pane windows and red and green lights to warn people if an announcer was on air. This seems like pretty small potatoes in this day and age, but in 1947 it was a major accomplishment. Consider the fact that snowball fights between the sorority houses was pretty controversial stuff, the campus blood drive was a major annual event and all the women had to be in their houses at 11 p.m.

January 1947 saw the beginning of KUOIs perennial function, a search for more funds. Again, the cry was heard. Hey everybody lets put on a show, this time for a dance. Launching an all-out fund drive, the staff, with help from the Business Administration Chamber of Commerce, raised $667.00 in two weeks. Always the optimists, the funds were earmarked to build a transmitter, new studio controls and buy more records.

The airwaves were not free from competition, however, and the men at Lindley Hall thought they might give KUOI a run for its money. With a short-wave radio and a phonograph, KLH went on the air. With no regular schedule and no manpower, KLH was not long-lived. A cozy relationship existed between the folks at KUOI and the Argonaut, and that helped the station gain listeners and compete with KRPL, the only local commercial competition.

Every new show idea KUOI came up with seemed to get coverage in the Argonaut. Whether this was good public relations work on the part of the staff or simply the nature of the campus camaraderie, not to mention the outcome of the fraternity system, is hard to say. A poll in 1948 gave an indication of their real PR effectiveness. Questioning students at three popular hangouts: The Nest, Bucket and The Spruce (everybody wasnt dry), the staff asked, How do you think KUOI could be of more service to the university? Delta Tau Delta member Bob Dahlstrom would have liked to have seen a course in radio announcing offered. Alpha Phi Jody Turner said, The announcers that try to sound funny should stop because they arent! Bert Sorensen from Sweet Hall thought they needed ASUI support and professional advice. Mary Clyde, Delta Gamma, said, . . . It has improved a hundred-thousand percent since it started!.

There were some things KUOI had absolutely no control over. Just about the time they thought they had a handle on equipment, some new breakthrough would force a modification in plans. An advertisement announced, . . .Plays up to 45 minutes! Now a complete album of music on one record (20). This was the advent of the long playing record. This was the first of many breakthroughs that would hit the recording industry in the next thirty to forty years and although the simple change over from 78 to 33 1/3 RPM would not present any major difficulty for KUOI. This was representative of why the station always seemed to be standing around with their hand out.

Under the leadership of smooth looking Harry Howard, KUOI would become a department of the ASUI system. The students had good reason to become a funded organization. The University of Idaho has, in its usual truculent manner, neglected communications as an academic field, and the students could see a need for training in this vocation.

Since its inception in 1945, 10 people had entered the professional radio world from KUOI. This was not bad, even for a fully accredited university department. Holding dances and fundraisers is all good fun but the truth of the matter was that they could not keep up with advances they were, in fact, $300 in the red. Howard claimed improvement in the station would be an asset to the whole university. A more professional staff and the chance of pay at the station would draw students interested in communications instead of keeping them away. Howard wasnt alone in his support for an ASUI radio station. The Argonaut backed the idea but not exactly for the same reasons.

KUOI had covered the Spur-IK boxing tournaments, an important sport in the 1940s. Howard Reinhart, one of the Argonaut editors of the coverage stated, That coverage alone was worth whatever it might cost us for KUOI . . . ASUI membership for KUOI would allow KUOI the progress it deserves. With this democracy at work, the Executive Board of the ASUI, in true bureaucratic style, named a committee to study Howards proposal. Seven days later, ASUI brought KUOI under its tutelage on a probationary standing. This meant Ted Cady and Glenn Southworth would get the money back that they spent out of their own pockets to get the station off the ground. KUOI would be under the guidance of the Publications Board and the station would now be an auxiliary to the university. Now, they would have access to war surplus equipment.

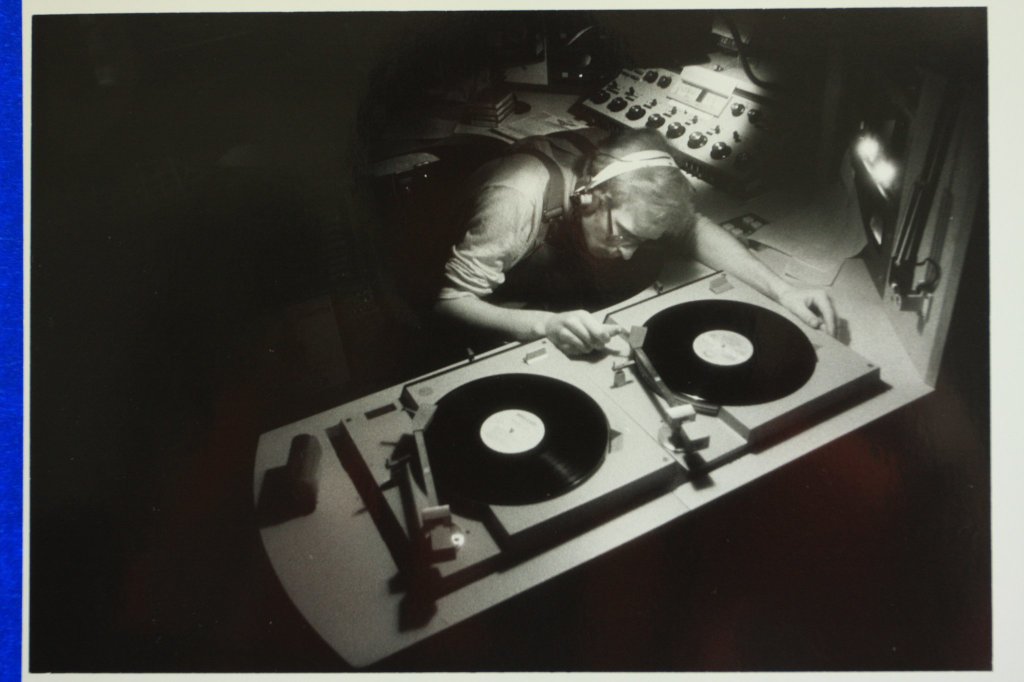

KUOI started to expand its operations, slowly but surely. It was already operating 13 hours a day but felt a need to improve its equipment. They had been moved out of the Engineering Annex and into a temporary building in the arboretum, which in those days was considered light years off campus, and Washington Water Power had installed some large transformers that interfered with the transmission. To handle the technical difficulties, KUOI relied solely on student volunteers. By February, the engineering staff had installed a new console, transmitter, new turntable and a new tone arm to play long-playing records. In an effort to solve the problems created by the WWP transformers, the technical staff was conducting experiments to see if it was possible to use the university water pipes as antenna. After leaving the air for a month while improvements were made, reception was reported to be much clearer. As an extra bonus to the students that supported the station through ASUI funding, the staff offered to record anyones voice who came to the stations open house.

KUOI had reason to be optimistic in its plans for a larger, better station. On the East Coast three colleges had pooled their resources to start the Pioneer Broadcasting System. Smith, Amherst and the University of Massachusetts were producing 69 hours of programming a week that they were able to put out to more than 11,000 people using a 40-watt transmitter. KUOI backers also cited the station at WSU as an example of what could come from a university station. At the beginning of KUOI history, the students were not particularly obsessed with its autonomy, only with the chance to have hands-on experience with radio equipment and practices.

Some things change and some things remain the same. Bill Hansen, in an editorial in the Argonaut entitled Customary Editorial, lamented the cynicism and apathy that led some students to abuse their rights. Their problem was that they chose not to vote in the ASUI elections. He characterized this minority as a group that finds fault with everything about ASUI . . . Some instances of this griping can be cited easily. KUOI, The Voice of the Vandals, is forever and a day being described as a hapless, hopeless, sorry attempt at trying to copy a borrowed idea. We have only one thing to say: since KUOIs beginning, the station has run on a shoestring sometimes that shoestring almost broke. Had it not been for a crew of ambitious staff members driving for a future goal, it would have collapsed. . . A proposed amendment to the ASUI constitution which would bring KUOI fully under the ASUIs executive wing, making it a department . . . will be on the ballot tomorrow. . . The Argonaut endorses very highly the passage of this amendment. . . The idea is if you have a justifiable complaint, why not do something about it. . . If you dont vote, keep your mouth shut nobody is going to pay attention to you. With passage of this amendment, KUOI moved again to a more official studio.

The 1950s were a time of expansion for everything in education, including the Student Union Building. Within the present SUB at Deakin and Sixth stood the old Blue Bucket. The old Bucket was a caf and soda shop where the gang could hang out. A $650,000 remodeling project transformed the structure partially to how it appears now. At this time KUOI moved into the studios on the third floor of the building. To celebrate the occasion, KUOI had a show especially dedicated to the SUB. In addition, the station would provide coverage of the Idaho-Montana football game. Further broadcast of UI football games would be a source of contention in the future. One of the antagonists in this battle was Gale Mix. Mix was an omnipresent feature on campus. He served in the official capacity of student manager, but in reality was found on most of the governing committees on campus. He was the source of advice for KUOI for years to come. Coincidently, one of his relatives owned KRPL and another was in the statehouse in Boise. One week after the broadcast of the Vandal game and the start of transmission from their new location, KUOI received notice that their signal was exceeding radiation limits as set up by the FCC. The immediate effect of this announcement was the shut down of the station until this problem could be remedied. The long-term effect was a poor signal that resulted from a decrease in power. The Argonaut was naively calling for bigger and better equipment. They, in fact, were hoping for at 250-watt transmitter unaware that Gale Mix, the ultimate arbitrator for all practical purposes, had little interest in seeing KUOI expand.

A slight push was on in Spring 1951 to have KUOI absorbed by the university. Don Hardy, editorial writer for the Argonaut, put forth the proposition that KUOI be more like its rival across the border in Pullman and integrate with the Communications Department. By making a radio announcing class, he felt it would prepare students for jobs on the commercial stations when they graduated from the course. State-operated radio was gaining popularity throughout the country. The flagship of the nation was WHA in Wisconsin. They had been in operation since 1918. WHA had its main studio in Madison and broadcast simultaneously over seven other satellite stations throughout the state. It differed from KUOI in that it stuck to an educational format. Therefore, KUOI offered no real threat to the commercial stations in Wisconsin.

Under the guidance of station manager Bob Burnham, Sigma Phi and Gene Hamblin, Sigma Nu, KUOI staged a minor coupe when they obtained a United Press teletype machine. Lucky Strike cigarettes paid for the machine with an agreement with KUOI to air two, 15-minute news shows with Lucky as a sponsor. In the 1950s and 60s it was not unusual for someone to actually want to hear news on the radio. Commercial stations were mandated by law until the Reagan era to broadcast the news twice an hour. Prior to the arrival of the teletype machine, the news was produced from local newspapers for a 15-minute weekday show that aired at 5:45 p.m. KUOI also made news itself. Requests for information were coming in from Spain, Peru, Brazil and Uruguay as a result of an article about amateur radio that appeared in Popular Mechanics magazine.

KUOI gained an even louder voice in the running of its affairs when an amendment was added to the constitution to give them a non-voting seat on the E-board, not that the station was unrepresented on the board in the first place. The fact that the station manager was in the Greek system gave him a good chance to be listened to whenever he had a problem. Out of the 16 seats voted on in the Fall election, 14 were won by the United Party, or the party of the Greeks. (Surprisingly, though, in a poll conducted by the Argonaut two weeks later, only 15 out of the 50 people they polled could hear KUOI.) The leadership of the student body by members of the Greek system reflects an acceptance of a certain kind of status quo.

The media and art are reflections of society. A UI professor polled 155 of his students regarding mate selection. The survey summed up the prevailing social mores of the times. In response to the question, What are your first prerequisites in the selection of a mate? The following answers were given: (in order of response) Men: be domestic, love home life, be honest, be neat in appearance, natural attitude toward sex, be a good cook, belong to the same face, pleasing personality, love children, be healthy, be affectionate, be able to communicate and free from physical defects. For women: Natural attitude toward sex, be honest, belong to the same race, pleasing personality, love children, neat in appearance, man be as tall or taller, the wife should be no older than the husband, have the same religious practice, be industrious, be able to communicate and be an interesting conversationalist.

Whether the class of 1951 followed these norms or not is for other researchers to discover. These responses indicated a Norman Rockwell vision that also carried over into their school life. Their political philosophy also reflected a motherhood and apple pie outlook. The University of Washington was under some kind of investigation by the Cawell Committee (one of many witch hunters at the time). It seems that certain professors have been, or were, connected to the Communist Party of America. The editor of the Argonaut wrote an article about the situation on the coast and was not concerned about the guilt or innocence of professors, but merely wanted to point out how gullible students could have their formative minds influenced. The writer stopped just short of advocating censorship. The solution was for American youth to know and understand the basic principles of democracy in order to form his own ideas on government. KUOI, coincidently, in the same issue, announced two new shows. One, the Student Radio Forum, would be discussing Federal Subsidization of Education, the other, The Junior Chamber of Commerce on Americanism,would feature a different speaker every week and run for 13 weeks. However, as the Argonaut editorial pointed out, most students are too busy to be bothered by political questions.

The 1950s was a period of technical struggle for KUOI. The move to the SUB had put back on the number of people that could pick up KUOI on their radios. Unfortunately for KUOI, the growing campus needed more and more electricity. This was a problem for KUOI because the station still relied on WWP power lines to broadcast the KUOI signal. Every time a transformer was encountered by the KUOI signal, a bypass has to be installed. Gene Hamblin, the station manager in January 1953, suggested that KUOI be piped into each living group. The KUOI staff was never completely daunted. If they couldnt broadcast to every student, at least the SUB could be wired for KUOI. So until the broadcasting problems could be overcome, the SUB would serve as an outlet for KUOI. The major obstacle to an increased broadcast range was the meager $710 budget. A second, and a more subtle hurdle that KUOI and every other form of media in the world had to overcome was the competition from television. KUOI hoped to go into the living groups on the same lines as television.

Television, pinnacle or dearth of modern civilization. . .made its appearance in the SUB. April 1954 was the day that television arrived on campus. Because of the primitive equipment of the time and the cost, $1,000, television sets were not common. Furthermore, interference from the large buildings on campus made installation of a large antenna necessary for operation of television. These problems made television ownership a hobby for the rich or institutions.

KUOI staff did its best to keep on top of the rating game. It was able to reach out to the living groups by installing a new $150 transmitter. More than 50 percent of the student body polled could now hear the programming. There was a 200 percent jump over the number of students that could hear it just a year before. The students also thought KUOI was still a good idea and that it offered a good training ground to potential radio professionals. Some even thought it should be linked to the University Radio Department. Luckily for the station, this was one student demand that was not met.

In the spring of 1953, UI announced plans to offer a BA in Radio Broadcasting. Course work was in recording and announcing, radio-television broadcasting and program planning and script writing. The first result of this change was the formation of the Afternoon Radio Guild. The Guild produced its first program that fall. It was about a mountain boy who received his first draft notice and surprised everybody with this uncanny ability to shoot straight. The Guild was used, for the most part, by KUID, the university television station, and went the way of all original programming on university-controlled airwaves.

KUOI was mainly a music station and the non-musical programming was either of the educational/forum variety or sports. However, KUOI had the jump on the Radio Guild. In October 1946, The Paulsen Playhouse debuted. It featured all original scripts written by Maurice Paulsen. The first drama was The Late Mr. Scareface and had two players in it. Fashion tips, Hollywood gossip, university musical chorales and Christmas shows were all popular through the years but the longest running event staged by KUOI was the Blue Key Talent Show. The show, initiated in 1948, was supposed to be a device to discover talent and showcase existing student talent. A sample of the program from 1950 reflects this philosophy; on double piano were Elizabeth Wilcox and Ellomae Holden, on electric guitar and accordion were Rich Davio and Pat Dumphry. There were piano solos, vocal solos, the Fiji Quartet (who were non-contestants because of their semi-professional status) and Mary Thompson, a toe dancer was unable to perform because of an injured ankle.

Through sports the staff at KUOI garnered their most loyal fans. It is no secret that the 40s and 50s were a male dominated era (women were very much part of the staff at KUOI as typists and secretaries, and occasionally as a player in a dramatic broadcast). Men dominated student government and the purse strings it controlled as well.

What could have been better than to sit in your room as hear UI student John Hughes said, its a left to the body and a right to the jaw, while Steve Emerine would do some color commentary: Well it doesnt look good for Jones. He came into this bout with a 3-1-12 record and it looks like hell go out with an unlucky 13. Boxing smokers were a favorite of ASUI General Manager Mix and a natural subject for KUOI sportscasts. Idaho was in the same conference as UCLA and the other big name West coast teams in the 40s and 50s, the Pacific Coast Conference, so the broadcast of football games was covered by the major radio networks. They were able to broadcast the home baseball games and the home basketball games. The ASUI was budgeting $101,040 for football and $28,000 for basketball in 1953.

Another favorite KUOI show was the KUOI Quiz Show. The quiz involved guessing the name of an old tune and calling in to win a carton of Lucky Strike cigarettes. The show would play the current favorites and occasionally an oldie would be thrown in so that the first caller to identify the tune would win the prize. The policy of the station at the time towards commercials was that only national advertising could be accepted. These oldies were still on 78 RPM discs at the time but an advertisement for Pullman Appliance and Music was a signal that the era of 78s was at a close. They offered, while they lasted, 78s for 49 cents each.

The 1950s were a time of live coverage for KUOI. It seemed that not an event could occur that would not have a KUOI announcer on the scene. Whether I was the Vandaleer Christmas Candlelight service or the Muckers Ball, KUOI was there. The effect of this policy reflected the democratic process that KUOI operated under. The wide diversity in programming was a result of an open door system of filling KUOI job vacancies. The openings would occur every semester as students came and went. This is KUOI, campus radio on the University of Idaho. . . may be drawled by radio majors or activity gals into its mics located in the Student Union Building, was the wording of the Fall 1955 call for help. KUOI would advertise in the paper that people were needed. The staff encouraged specialty shows and would try to provide the technical and engineering support necessary to execute a show.

1954 saw the beginning of a perennial KUOI ceremony. This was the beginning of the stringing of the wires to the living groups. KUOI would string wire in the heat tunnels or on telephone lines to reach each and every living group and the often heard recant, We hope to reach every living group by next year! would be chanted by the station manager at the annual ASUI Budget Meetings. The wire was like an extended antenna and any receiver within 250 feet could pick up the signal. The wire to do the project was donated by the Electrical Engineering Department.

The Engineering Department was not the only department to cooperate with KUOI at the time. The Communications Department had not yet constructed KUID as its practice station so the Radio Guild worked with KUOI to produce programs like Here We Have Idaho. This show would feature prominent Idahoans when possible or UI people talking about Idaho. It would be transcribed and sent to stations all over Idaho for replay.

The office girls were finally allowed to do a little broadcasting in 1958. The show entitled The Feminine Touch aired between eight and noon on Saturdays. On Fridays a show began called The Blind Date. KUOI was to play cupid every Friday for a half an hour.

The advent of Rock and Roll was slow in coming to KUOI. In a poll conducted by KRPL, UI students came out 10 to 1 against Elvis Presley. KUOI was more likely to play jazz or folk through the 1950s.

However, 1958 saw the end of any serious classical programming. The late 50s also saw the demise of drama on radio. Television was in full swing by 1960. Most radio networks had abandoned dramatic presentations in their schedules. The transistor radio now put radios in anybodys hands anywhere they wanted to be. KUOI was in the command of Larry Ayers, one of the more energetic and political station managers that would occupy that position. Ayers was faced with the same old problem of bad reception as his predecessors. He tried to resolve it by placing transistor mini-transmitters all over campus. Ayers also campaigned to win a new sponsor for the AP teletype service. Although there wasnt any record of dissatisfaction with the all-music format, the Argonaut was pleased to hear the straight music format would be broken up with news every half hour.

Fred Otto introduced a new style of announcing that the nation would grow to despise over the next 20 years. Dynamic announcing was the name given to the style that would characterize AM radio for all of its rock era. On a non-commercial station like KUOI, the style had its advantages. Otto would announce songs with a minimum of talking, all fast and explicit, but on commercial radio this style would let the announcer read as many commercials as they possibly could in the time between tunes. On KUOI, Otto was able to play a record amount of songs the first night he initiated the new style. The effects of mass communication also reflected in the new styles. Jerre Wallace asked that DJs use a moderate tempo when announcing, but also asked that they limit the personality touch that many DJs tried to put across. This attitude depersonalized programs and announcers. It trained students to be part of the machine, faceless and nameless, ready to replace any part of the communication system when they graduated from school. The Radio Department now would use the station as a lab every morning from 8 a.m. to noon for radio majors. The university was a factory in full production.

The early 60s were not reactionary at the University of Idaho, but UI was hardly a paragon of Camelotian virtue either. While President Kennedy was doing the twist on the White House lawn, KUOI returned to classical symphonies, semi-popular music and a minimum of rock and roll. This policy helped KUOI stay in the minds of the student government. There were enough rock n roll and twisting stations in the area, according to Argonaut editor Herb Hollinger. The mission of KUOI was to reflect as institute of higher learning. The competing parties for the student senate at the time seized upon the issue in the spring elections. Each claimed to be the better patron of KUOI. Jerre Wallace was a little more realistic, if not downright pessimistic. He pointed out that if KUOI was to compare with WSUs KWSC then it was going to need a very expensive transmitter. Furthermore, the production time and materials necessary were not likely to be forthcoming, considering the miserly allotment from the E-Board. KUOI had been operating on a budget of $1,100 since 1955.

In yet another attempt to jerry-rig an all campus station, KUOI went off the air from May 1962 until March 1963 while more wires were strung to each and every living group on campus. The station had been delivering a good signal before the shutdown, so good in fact that it was going off campus and into the domain of KRPL. The FCC inspected the situation several times and told KUOI to fix the problem. Also, the KUOI technical staff and volunteer engineering students had to design new auxiliary transmitters and assemble them from scratch for each living group.

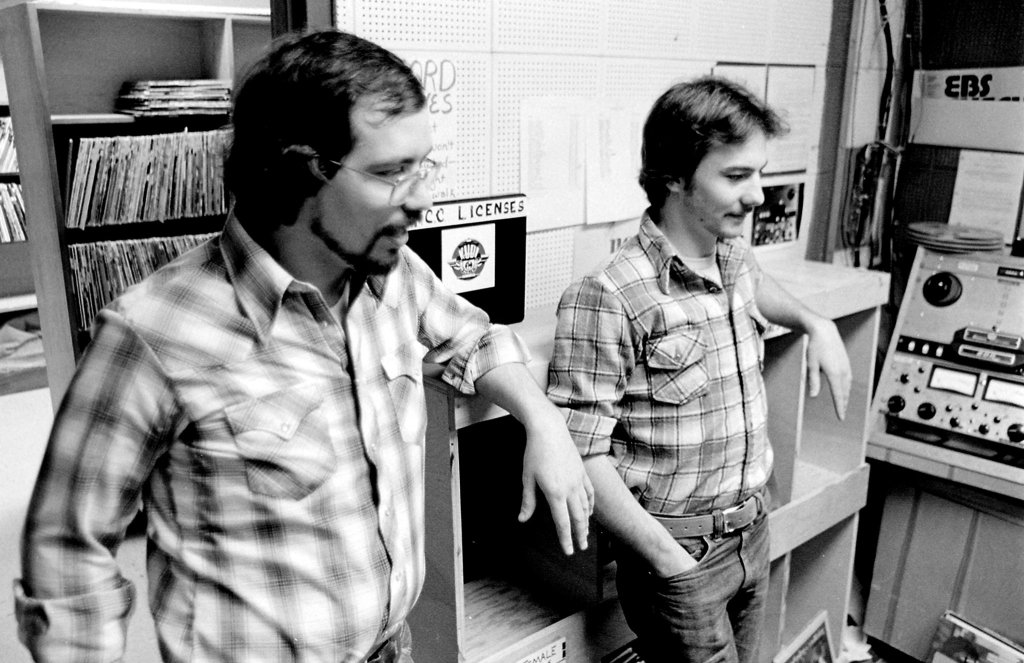

KUOI was not the only radio station on campus when it went back on the air. Station KTRS-FM opened at the same time. This was what would later become KRFA. KTRS was to provide the radio training that students needed to enter the communications field. It would also provide more educational type programs. KTRS flourished for a few years, became embroiled in the KUID controversies and was converted into a relay station for KWSC in the early 1980s. There was a small glitch in the start-up of KTRS, one that may not have been straightened out at the date of this writing. The FCC has a clause in its rules and regulations that prohibit an entity from owning two radio stations in the same broadcast area. For this reason it was made clear to the FCC that KUOI was indeed owned by the students and not the state of Idaho. The FCC accepted this and KTRS went on the air. The full ramifications of this decision have never been fully explored.

Despite the best efforts of the KUOI technical staff, the new broadcasting system did not perform as well as expected. KUOI was given a year to clean up its sound or face the budget axe in 1965. KUOI had been operating in an on and off mode for nearly three years when ASUI really got serious about funding cuts add that to the fact that KTRS was fulfilling the role that KUOI had aspired to for most of its history. However, when KUOI finally got the newest system off the ground it worked better than expected. Despite foot-dragging by ASUI General Manager Gale Mix, KUOI was able to keep afloat. Alvin Burgemeister, station manager, rallied the support of students through aggressive public relations and popular call-in shows. The new shows let students air their thoughts and gripes over the air. In retrospect this small move on the part of KUOI was the beginning of a student rights movement that reached a crescendo in the later 60s, and has yet to fully recede. Moscow, Idaho is a long way from Berkeley, Calif., but not so far away that events there went unnoticed.

In the fall of 1964, Mario Savio led students in the Free Speech Movement (FSM), which was the product of a repressive administration at UC Berkeley. The students had attempted to distribute political information early in the school year on campus. The university denied them that privilege and the FSM was born. Interestingly, the rule that prohibited political solicitation on campus was not the result of anti-communism, but had been enacted after William Scranton did some campaigning on campus in the spring during the Republican National Convention. Someone from the Pro-Goldwater Oakland Tribune complained that the Stanton people had not followed the proper channels to get permission to work on campus. The result was a ban on political action on the UC Berkeley campus. The argument could be made that in-fighting by the Republican Party caused the FSM and everything that grew out of it the Establishment can always be trusted to turn out radicals despite itself.

These events were taking place in the fall of 1964, well before the anti-war protests began. In fact, the first members of the FSM included Young Republicans and Young Democrats. The Argonaut backed these protests and KUOI started its student opinion programs. Rock and Roll, the mainstay of commercial radio at the time, was allotted two to four hours a week on KUOI. Folk music and lighter study music dominated the KUOI airwaves. The mission of the station was laid out by Jim Kuehn, chief announcer, . . . to communicate with students by bringing them closer to events happening right here on their own campus. If we communicate, then we get students thinking weve accomplished our goal.

KUOI stuck its nose into campus politics in the 64-65 school year. The live remote broadcast was still popular at KUOI and these remotes included the ASUI meetings. KUOI had nothing to lose by going after the senate the senate had nearly done away with KUOI the summer before. KUOI Feedback was a call-in show that would let the students state their opinions about the nights meetings. They went a step further when KUOI put a ballot in the Argonaut letting students give their opinions on how they thought ASUI should spend its money. KUOI had a budget of $925 and was not happy about it. KTRS had attracted most of the radio majors so KUOI felt since they served a general student body representation, they deserved more money.

1965 was the 20th year of KUOI transmissions. It was the only student-owned and operated station west of the Mississippi. Johnnie Mathis was slated to perform in Memorial Gym, and talk of Vietnam was first entering discussions on the UI campus. All the while, FM radio was coming into its own. FM was thought to be the best, next step for radio broadcasting. FM transmission meant that stereo, which was also gaining popularity, could be broadcast and for KUOI it was important because KUOI could now increase its range without violating FCC rules.

The folks at KUOI, station manager Larry Seale specifically, wanted KUOI to break new ground by playing popular, rather than classical music on FM. Seale had to write a letter to President Hartung and request permission to go FM. Seale pointed out that KUOI did not need to license each and every one of the announcers, the KUOI would be incorporated so that it would not violate the FCC dioplot rule, (this rule stated that two stations could not be owned by one entity), that the organization of KUOI would not lead to any conflict of interests and that the station already confirmed to all FCC regulations. Tom Neal of KTRS felt his toes were being stepped on he responded that KUOI would be in violation of FCC rules and that the students who operated KUOI were simply too amateurish to operate an FM station.

Not all the administration was opposed. Charles Decker, dean of students, was in favor of KUOI incorporation as long as the E-Board approved that the station served the educational mission of the university. Furthermore, he expressed the belief that the funds for the switchover, estimated to be about $1,000, could be transferred from the ASUI general reserve. $4400 was allocated to KUOI in spring of 1967 in expectation that KUOI would be stereo very soon. This sizable allocation of money was mostly attributed to the skills of Larry Seale.

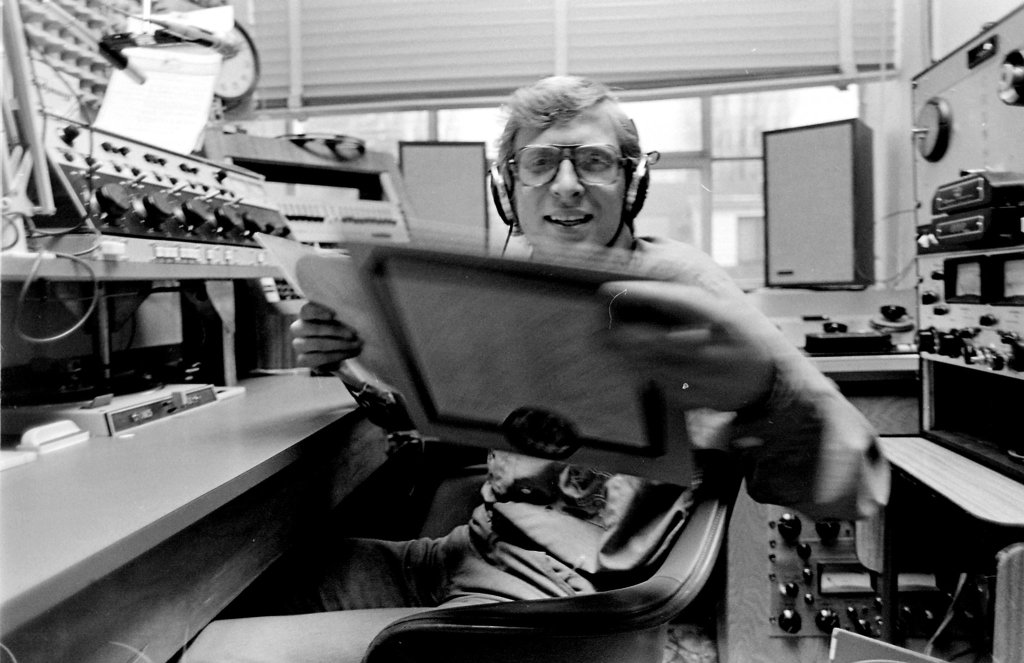

Larry Seale was an exceptional station manager who had astounded everyone by doing an end run around Gale Mix to finally allow KUOI to solicit for advertising. Mix, ASUI general manager, had told the ASUI that it was illegal for KUOI to solicit advertising for years. Seale, in the spirit of the times, decided to question authority. He went directly to President Hartung and asked him to find out if the Board of Regents had any problems with KUOI soliciting advertisements from local businesses. The Regents replied that they had no problem whatsoever. Seale also redesigned the station to operate more efficiently. Much of the new equipment that was purchased that spring automated many routine tasks. For instance, now public service announcements werent prey to the diction mistakes of every announcer they could be recorded clearly and played back at the desired time. KUOI went FM in November of 1968. The Student Sound was folk music, jazz, up-tempo rock, comedy and former hits. The station was no longer limited to campus living groups, but served a 10-mile radius.

KUOI and the Argonaut were not very fast in catching on to the underground. The improvements that Seale introduced attracted potential radio professionals that wanted to work outside the control of the Communications Departments professors. A student could only take so much classical music and radio classroom shows. In 1970 KUOI switched to a kind of top-40 format, a precursor to the album-oriented rock of the late 70s and 80s. While stations in San Francisco or Chicago were catering to the underground The Velvet Underground, Electric Flag, Led Zeppelin, Iron Butterfly or the Soft Machine, KUOI was still airing Sounds Like the Navy, a Navy Department PR show that would feature safe rock like the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. John Foley, a DJ in 1970, reviewed After the Gold Rush, an album by Neil Young.

Young was one of the original underground musicians. One of the campuses freaks, the euphemism used in the 60s and 70s to describe counter culture types with long hair, had requested that one of the songs be played. The song, Look at Mother Nature On the Run, Foley determined to be about a wish to return to the golden days of feudalism. Foley also determined that hippies were simply a latter day populist Don Quixote, . . .charging the windmill of America (sic), seeking a father. Foley wasnt really anti-hippie, but he expressed a certain amount of reservation regarding their motives. The decision to remain top-40 was based on the idea that this was what the students wanted. Non-musical production were to be more controversial and an attempt would be made to cover campus news and issues in depth. The first show covered the finances of the Student Bookstore. The Argonaut, however, had decided the revolution was at hand and that business as usual was ending. They announced that it was no longer going to report on who pinned who and announced the end of fraternities and sororities. This was also the end of a cozy relationship between KUOI and the Argonaut.

So, while the Argonaut took up the banner of the radical student-left, KUOI sponsored Frisbee tournaments, concerts and covered the sporting events. Robie Russel was DJ and head of the Vandal Boosters (the most important department on campus during the Gibb years) at the time he would later become the chief of the EPAs northwest division under Reagan (he resigned after it was found that he was nothing but an industry lackey). The editor of the Argonaut and a former station manager had to take KUOI before the Communication Board to convince it to give equal air time to groups opposing the war in Vietnam.

The resistance to the top-40 format was beginning to build. KUOI featured a non-stop kind of musical delivery that came from a playlist devised by the KUOI management. The protest reached a peak in the spring of 1972. Listeners felt the station pandered to teenagers and that a more intellectual station was in order. Diversification, which in later years would become a KUOI motto, was what students were demanding. The only show that varied very far from mainstream was one titled Total Black Experience. The DJ, Jay Wheeler was allowed total freedom in the selection of his show. The intransigence of the program director was brought to light when Jack Scarbourough was fired from the station. He had made the mistake of playing country-western tunes on his show. He pointed out that the listening public wanted something different, as demonstrated on the Wheeler show. He also called attention to the fact that a country-western band, Hog Heaven, played to a full house at the Coffee House, while one of the ASUI concerts by The Grassroots played at Memorial Gym (these concerts were perennial failures). The top songs played in fall of 1973 were from Deep Purple, Elton John, Brownsville Station, Chicago and Gilbert and Sullivan, the mainstays of top-40 at the time.

Steve Woodard, station manager at the time, defended that KUOI policy. He said the station played songs only once every five hours, in contrast to the three-hour rotation of commercial radio. The policy was based on the belief or theory that most listeners only tuned in for short periods of time to hear their favorite song. It only took a phone call on the request line to have a song played. The record library had 1,000 singles and 1,200 albums. Whether his response was valid or not remains in question. There were more than 5,000 song titles to choose from in the 1950s. The KUOI playlist had only 30 singles and six albums to pick from at the time.

KUOI became embroiled in campus politics in April 1974. There were still black students on campus in 1974 who were not athletes. They had a club and a building west of the SUB, where the present Theta Chi house now stands. The Black Student Union finally got tired of UI foot-dragging on affirmative action and made up a list of demands. The demands were presented on afternoon when members of the Black Student Union took over KUOI long enough to read their demands. No action was taken against the Black Student Union because no resistance was put up by the people at KUOI at the time. The Black Student Union demanded that minority members be hired by the administration to fill posts in admissions, financial aid, athletics and faculty. The administration replied that they had just hired a minority and had just begun to scratch the surface. KUOI stepped on a nerve when they attempted to record a tenure appeal hearing.

Dr. Willis Rose had been denied tenure and an appeal was under way. The meeting was open to the public and was, in fact, being recorded by the appeals committee. A KUOI reporter asked for access to the tape but was denied. Therefore, the reporter went and got their personal recorder. The committee was alarmed at the presence of an outsiders recorder and voted to have the KUOI recorder turned off. John Hecht, the KUOI reporter, called around the state for a more official ruling on the matter and was eventually informed that President Hartung himself had agreed to the presence of reporters in the room. However, in true UI fashion, he would not overrule the decision of the committee.

1973 also saw the attempted rearrangement of the Communications Board. The Communications Board was the ultimate arbiter in KUOI matters. The problems in the Communications Board stemmed from the Argonauts radical editorial policy and the reactionary policies of KUOI. Some students complained about each department the Young Americans for Freedom complained about the Argonaut and the campus radicals complained about KUOI. The Communications Board had been rearranged in 1972 in a way that favored the personal tastes of the ASUI president. In 1974, a new plan was introduced based on a proposal by Lewiston Tribune reporter Jay Sheledy. Sheledys plan was most ambitious, but probably should have been introduced in the mid-60s. The 1970s were not a particularly exciting era for journalistic advocacy and the need for freedom was never exploited. Sheledys plan called for two media professionals to sit on the Communications Board as advisers, one of which would be elected by the students as the chairman of the board and five students, on appointed by the student president, the rest elected in staggered terms. Furthermore, they would not be under the wing of the executive branch, but would instead be autonomous.

KUOI had been under the guidance of Don Coombs for some time. Coombs was chairman of the School of Communications. The senate had some reservations about Sheledys plan but approved it anyway. Although Sheledys plan said this would free the campus media from un-due political influence, the reality of the situation was that one of the print professionals would have to come from the corporation that employed Mr. Sheledy. The owner of that corporation in 1973 was also on the Board of Regents for UI.

The KUOI format question came to a head in 1974 amid charges and counter-charges. In spring of 1974 Matt Shelly, station manager, was accused of inappropriate behavior when it came to light that he had loaned the KUOI teletype machine to KRPL over the Easter break. Shelly worked at KRPL and a conflict of interest was cited with his employment at KUOI. He also received a free airline ticket from KRPL supposedly for this favor. Although it was never proven, it cast a shadow over his administration. The following fall Doug Jones was dismissed from his DJ position because Shelly said his show didnt go over. Shellys conclusion was not based on any sort of fact and student reaction to Jones firing reflected an overall dissatisfaction with the continued top-40 format of KUOI. The question that was presented to the Communications Board was: who decided each shows format the DJ or the station manager?

The staff of KUOI was also split. The assistant music director and the traffic director both agreed that Jones had been fired unfairly. They also pointed out that two other DJs, Eric Larsen and Kim Wellington, had also been dismissed arbitrarily. Eventually, Jones got a hearing and was reinstated. The sounds at KUOI remained in a mediocre rut. Bill Harlan was named new station manager and some students feared he would wallow in his obnoxiousness and turn more listeners off the airwaves, keeping in the fine tradition of his predecessor Matt Shelly. The attention turned off KUOI for a while because KUID radio decided to go progressive. Those students who wanted to listen to other types of music than top-40 had a choice. Even KRPL saw the light and started its own New Music on Saturday nights.

Bill Harland disappointed the naysayers at KUOI and on campus. He introduced a vigorous PR campaign that included aggressive anti-administration editorials, new recording equipment and new ideas in programming. He put the pressure on DJs to work up specialty programs that had more -substance than the all-music format of his predecessor. The local news had eight reporters covering town and campus. Every night students could hear a new album in its entirety at 10 p.m. A number of shows would highlight different artists and talk about their music, something that never happens on top-40 radio. The biggest achievement under the tenure of Harlan was the switchover to full stereo.

In the spring of 1975 Harland may have been conservative in the eyes of the average radical of the times but these folks were living in a kind of never-never land that did not reach dominance in North Central Idaho. Harland realized if the funds to upgrade KUOI were to be obtained, he would have to work with the administration and please the students at the same time. Harland could see that the ASUI Senate would never come up with the estimated $40,000 necessary to buy a large enough transmitter to allow stereo broadcasting. Harland found the money he needed in the SUB bond reserve. Harland then reached a deal with the Communications Board and the Argonaut. The entire communications branch ASUI would move into a remodeled third floor of the SUB. KUOI was already up there and the Argonaut jumped at the chance to get out of the basement.

Administration support was all but guaranteed when Financial Vice President Sherman Carter said using the reserves is financially feasible and legal. Even though KUOI did not go stereo until January 1978, Harland can be credited with getting the station over the financial hump.

The musical fare in the middle and late 70s could hardly be described as underground. The era of top-100 albums was coming into its own. 45 RPM singles were losing favor to 33 1/3 LPs, as stereo equipment improved and the automatic record-changer became a rarity. The major labels were now pushing artists that didnt necessarily have hit singles. The songs could now be longer than three minutes as well. There was not one song that was even three minutes long on the Beatles 1963 Meet The Beatles album. Furthermore, every song on the album was released on a 45 RPM single before the album came out. The change in marketing by the major record labels brought artists like Leo Kotke, Flo and Eddie, Jerry Jeff Walker and a Fleetwood Mac spin-off, Paris, to the nightly album preview. KUOI also continued aggressive PR by advertising heavily in the Argonaut.

PR for KUOI was the most inconsistent part of its overall operating policy. During some years schedules and program features would be printed on a regular basis in the Argonaut and other years there would not be a trace of KUOI unless the station was in the midst of financial difficulties. The blame can be laid at the feet of both the station manager and the Argonaut editor. The option of what to print or what not to print has always been an arbitrary decision of the Argonaut editor this is the nature of the editors job, but what defined the universe of campus news varies from editor to editor. Whether KUOI fell in that universe or not was most often determined by the number of KUOI staff that overlapped with Argonaut staff. In the early years of KUOI history the overlap was quite considerable. In the late 1960s and early 70s, ideological schisms developed and there was virtually no overlap. The mid-70s saw a renewal of communications program unity, not to the mention a closer physical proximity on the third floor of the SUB.

The fact that KUOI had experienced a change in ideology is evident in the non-musical programming aired in the mid to late 70s and beyond. Special programs like the National Lampoon Radio Hour, Firesign Theater radio series or a KUOI production of a Stokely Carmichael press conference went to great lengths to criticize or satirize the U.S. government. Public Service Announcements also reflected a certain non-establishment interpretation of the stations charter from the FCC to serve the public interest.

A great deal of the public service announcements aired on radio and TV are sponsored by the Advertising Council, a PR institution reflecting the philanthropic conscience of the corporate elite. KUOI was airing PSAs from groups like the Public Media Center, and groups like these would often and still do come under fire for being biased. In spring of 1977 the station began to carry a PSA that was highly critical of the nuclear energy industry. The criticism was deflected by KUOI by an aggressive pursuit of an opposing viewpoint. Station manager Tom Rafetto said they had contacted 96 people in one week to find an opposing viewpoint to an editorial opposing the construction of the B-1 Bomber and could not find a single group or person willing to make an opposing PSA.

KUOI finally went stereo in January of 1978 under the guidance of Chris Foster. The station had leapt over hurdle after hurdle to reach this point: bad equipment from the manufacturer, new antennas installed and financed, programming hassles and numerous personnel changes. The station finally became a state of the art facility with little or no help from the administration. The Board of Regents announced in March of 1978 that they should now hold the license of KUOI. They had come to this conclusion after a study had been commissioned to investigate state-owned media. One of the mentors of National Public Radio, the milque toast, vanilla milkshake, vision of what responsible public broadcasting ought to be, conducting the investigation and came to the conclusion that the Regents were ultimately responsible for what went over the airwaves from the KUOI studios. The fact that there had never been a dispute involving KUOI in 30 years of broadcasting did not matter, the Regents wanted control and got it. The Board of Regents now had ultimate authority over all state-owned radio in Idaho. This included the student station in Boise. Although the station was never owned by the students they were allowed to operate it from 1977 to 1988. In 1988 the Regents stepped in and took away the station from the students and had the new managers broadcast 200 to 300-year-old music that originated in Northern Europe and was written by men (Aryan Folk Music?) in other words the regular NPR fare. The bottom line to the new Regent position concerning KUOI was that they ultimately had the final say in selecting the station manager. This did not sit well with the students.

The rebellion, again the new Regent police, was led by none of than the UI parking czar of the late 1980s and early 90s, Tom Lapointe. He was the first person to realize the possible ramifications of Regent control. The record of past Regent takeover of student facilities was easy enough to illuminate. The most glaring examples of Regent thievery were the Kibbie Dome and the golf course. Both of these facilities had been paid for with student fees extracted from the students with the understanding that the students would be in control of facility management. The Regents had placed Don Coombs as the institutional liaison to the station. Coombs was communications department chairman and was also in charge of KUID. The president of the State Board of Education claimed UI students were crying wolf. Supervision was not the same as censorship and the Regents open door policy would prevent Regents from becoming censors. He then said the most important thing for the students to try to come up with was an independent Communications Board. He also said the Argonaut would not have an adviser.

Dennis Haarsager of the Idaho Public Broadcasting Committee attempted to lay the blame at the feet of those that had put the Board of Regents on the FM license application. The ASUI Senate responded to the situation by passing a resolution that asked the Board of Regents to give the power of the station manager appointments to student advisory boards. The board merely backed off in any attempt to appoint an institutional liaison since Coombs supposedly held an advisory position in the first place.

The ASUI Senate appeased the Board by writing in a clearer job description for the station manager that included language that the station manager be familiar with, FCC rules and bureaucratic chains of command (124). KUOIs editorial content never was mentioned in the dealings with the board. The musical format was not too esoteric for the average listener, either.

KUID, the other student station on campus, was bending over backward to not offend the Committee for Public Broadcasting. It had switched to the adult contemporary format this was and is sometimes referred to as elevator music. KUOI tried to serve the students by playing new releases and requests, plus football games. Sixty percent of the student body said it listened to KUOI, but KUOI was under fire for bad fiscal responsibility. It had managed to spend its entire budget in the fall semester. The ASUI had cut back the budgets for all departments and the manager in the fall had quit during Christmas vacation. This left the new manager for spring of 1979 holding an empty bag. Other departments, like the Outdoor Program, were clamoring for the axe to fall on KUOI. The senate kept a somewhat-objective perspective on the whole manner but picked a new station manager that did not sit quite well with station volunteers.

Besides the money matters, there was some concern from community members about what was going out over the air. Chris Foster defined the KUOI mission going into the 1980s. He felt KUOI was an alternative to AM radio and they were there to promote community events and to serve the public interest. Controversy could not be avoided but profanity should be: . . . if people want to hear trash they can tune to any number of top-40 stations, Foster said, . . . think of it as your granny listening or your little sister. Foster was replying to people like Dr. Thompson. Thompson had complained about the content of the Firesign Theater broadcast, which was usually satirical and always irreverent. Foster said he welcomed opposing viewpoints and that KUOI tried to offer an alternative to mainstream radio. What about Brett Morris, the manager that the ASUI president appointed over the objections of the KUOI staff? He lasted two weeks before resigning.

KUOI came under a cloud as a result of the manager controversy. They would stay under that cloud for most, if not all of the 1980s. Steve Cuddy, in a letter to the Argonaut, set the lines of the long running battle. He felt KUOI was not serving the interests of the students. He called for a survey to determine student preferences, more variety in music and more non-musical programming. The music director, Hugh Lentz, replied by stating the facts: KUOI had musical variety and pointed out that a station run by volunteers was not capable of big production shows. Furthermore, Lentz felt if KUOI programming wasnt up to Cuddys standards that he should volunteer for a few shows himself.

Nevertheless, Tom Neff, the station manager from 1979-80 school year tried to be more creative. He widened sports coverage by having interviews with the Vandal player of the week. This was a good way to gain the interest of at least 44 very large listeners and all their friends. He tried to program the same kind of music to the same time every day, . . . no more acid rock in the morning. Space Reports, a show produced by NASA would now be a regular feature. The foreign students had their own show, as did the women, children, composers and authors. Neff was being a true Democrat. However, the ASUI president and senate were still in a fury over the earlier station manager controversy.

Neff had organized a club called KUOI-Graphics, which raised $85 for KUOI. Scott Fehrenbacher, acting on the advice of ASUI Attorney General Dan Bowen, said KUOI-Graphics must give all of its money to the ASUI Senate and dissolve immediately. Otherwise, Neff would be censored, fired and impeached, and KUOI funds would be frozen. The problem was solved after a public hearing during which Neff agreed to turn the graphics money over to the University Foundation to be given to the station at a later date.

Despite Neffs attempts to widen the stations format, Fehrenbacher won in the end. Gary Spurgeon was approved as KUOI station manager by the Communications Board but Fehrenbacher vetoed their choice and nominated Jenifer Smith instead. Smith promised to put KUOI on a full top-40 format. This resulted in the resignation of the Communications Board Chairman Monie Smith. Jenifer Smith conducted a poll and came to the conclusion that top-40 was what the students wanted. New wave was to be the thing of the past. However, even J. Smiths tastes in music were not mainstream enough for some on campus. There was still a huge cry from the populace for a change. An open meeting was organized but it turned out the only people who showed up or cared enough about KUOIs format were a gaggle of Phi Delts. Little changed as a result of the meeting. Smith was able to hold off the masses by allowing living groups their own shows. Each week a different living group could come on the air Thursday from 6-10 p.m. This kept the living groups happy and not a peep was heard for another four years.

KUOI stayed somewhere between the underground and top-40 during the early 1980s. The station was rated 7th out of 1,000 radio stations by recording companies, and partly because of the Berkeley College of Music selected KUOI to help in the selection of five $1,000 scholarships that it had to award. KUID-FM, on the other hand, was being handed over to WSU Dennis Harsager, former head of the Idaho Public Broadcasting Committee, who arranged the deal with WSU. He felt KUID was not what an NPR station should be and that changeover could give students some hands-on experience. Things changed in March 1985.

ASUI Senator David Dose took it upon himself to conduct a survey. He handed out 200 survey forms to get a feeling of the students regarding student programming and got 50 back. The results of the survey showed that the students felt only 9 percent of their student fee should be spend on KUOI and that 26 percent should be spent on academics. Based on these figures, Dose and company set out to completely change or destroy KUOI. What Does and friends failed to prove was that by law, fees cant be spent on academics that is called tuition. Furthermore, out of an average $500 fee, a share to KUOI of 9 percent would equal almost $50. Therefore, based on the enrollment of 9,000 students, KUOI would have to have its budget increased to $450,000. Dose led a campaign on a phony poll and fictitious numbers, which would reach a crescendo over a year later.

Dose was merely a reflection of nation and state politics of the times. The recession of the early 1980s led many politicians to the conclusion that anything that originated before 1980 must be a waste of money. Dose simply wanted to mimic his adult counterparts in real life. KUOI wasnt the only program he wanted to axe. He went after the Outdoor Program, the Argonaut and Lecture Notes as well. Interestingly, the poll showed that the students wanted 17 percent of their fees spent on student government. If all the programs were to be cut, however, there would not be any reason to have a student government. The station manager for 1984-85 was Chan Davis.

Davis and Dose hailed from Pinehurst, Idaho and represented both extremes of the political spectrum. Davis had forbidden the playing of any top-40 on KUOI while she was station manager. She let the DJs have total control over the formatting and station management. Unlike Dose, she thought the best student government was no government. The thought of listening to any tinhorn student politicians telling her what to play never entered her mind. Doses campaign resulted at first in the hiring of Greg Meyer.

ASUI president Jane Freund was fairly oblique in her assessment of the problem. She was concerned about the controversy and wanted to talk to the Communications Board about it. Even more obtuse were her references to income-generating programs and the need for the ASUI to move toward self-sufficiency. The term of the president runs from January to December. The term of the Communications Board runs from September to May with some overlap of incumbent members. The new station manager could be selected by the Communications Board that Freund had little control over. They picked Meyer for station manager for the 1985-86 school year. Meyer could see the writing on the wall but also knew that for the most part KUOI was little different that it had ever been. Meyer started a PR campaign to reshape KUOIs image. He had the help of the Argonaut editor John Hecht. Hecht had been a KUOI supporter for years. For the next year Meyer would introduce new programs and the Argonaut would publicize them and mention old ones that were an asset to the community.

KUOI had a record library for 15,000, broadcasted the Renaissance Fair live and was now willing to open its doors to anyone with good programming ideas. Class closures were announced live from the Dome when students would register the next fall. Meyer announced an expansion of the KUOI News Department and that students could earn class credit by becoming reporters. Meyer had done a good enough job in changing the stations image that he was granted $6,000 to buy some new equipment. Meyer attempted to put an end to the stations punk-only image. He guaranteed that punk would not be served during the breakfast hour.

The musical format was widely varied with classical, jazz, rock, reggae, big band, blues and new wave. Live from the Lobby featured performances by local entertainers every Thursday night. Every Monday night KUOI Sports Center would analyze the Vandals performance for the past week. Meyer did the best he could to broadcast what the students wanted. However, another poll taken by the Argonaut during the spring 1986 registration cast a shadow over Meyers achievements.

The new poll was reminiscent of polls taken throughout KUOIs history. The poll showed that although most students did not listen to the station, continued funding was still approved. Fifty-nine percent of the students polled said they rarely or never listened to the station. Thirty-seven percent felt that funding should be withdrawn from the station. The poll failed to say what stations the students did listen to or if they listened to radio at all. Also, no comparison was made between KUOI ratings and that of any highly successful commercial stations.

The release of this poll in late March 1986 caused KUOI operations to become an issue in the spring senate elections. The Communications Board started to respond to renewed student interest in the debate by suggesting an even greater improvement in the KUOI image. Recommendations included building a closer relationship with the School of Communication, better training of KUOI DJs, a professional survey to determine what the students wanted to hear on KUOI and/or changing the stations format. Meyer agreed that a closer relationship with the School of Communications could be worked out over the summer. At this point the senate decided to take some action.

In late April Gino White, ASUI president, appointed Rosellen Villarreal-Prince as station manager, following the recommendation of the Communications Board. The senate voted its approval after a heated argument. The new manager was planning to change the station to top-40.

The debate in the senate that day concerned what the ramifications would be after Villarreal-Price took office and why she should be hired in the first place. ASUI Vice-President Piece said if the administration thought the senate was not handling KUOI right, then maybe they should take over. Senator Brian Long wholeheartedly supported her appointment and cited her achievements on the activities board as an example. Paul Aillee said her qualifications were in order, that she went through the process and that she should be approved. White said KUOI DJs who were against Villarreal-Price were probably not thinking of the student body as a whole and Davis pointed out that Villarreal-Price was urged to ask for the job by White, Long and Aillee. The senate voted to approve Villarreal-Price as manager and paved the way for a long, hot summer.

Station Manager Greg Meyer started the anti-Villarreal-Price movement before she was even approved. He claimed she had worked at the station in 1982 and quit because her top-40 programs were not allowed at the time. He also said her appointment was the result of a few senators with an axe to grind, and that the other applicant to the position did not nod his head to the Communications Board during the selection process.

Meyer was 34-years-old and not given to ASUI politics. B.J. Hargrove, another 35-year-old graduate student who had worked at KUID and did a jazz show on KUOI, started a petition to reopen the position of manager because of the handling of the selection process, which she characterized as unprofessional. Before the dust cleared, Alan Lifton and Coombs were moving in to work out a co-op between KUOI and the School of Communications. They were in need of a training facility now that they had given away KUID-FM. Letters to the editor in the Argonaut came in fast and furious.

Lifton had made the mistake of saying that KUOI sounded like a bunch of college kids playing around with radio equipment in the same breath as saying that he tried to avoid listening to KUOI. Neil Franklin, UI law professor, chastised Lifton in a letter to the editor by saying that even though some DJs might sound downright silly that the faculty should encourage innovation and growth.

Villarreal-Prices reign began without too much resistance from the DJs but she began to take actions that would come back to her. First, she cut the 2-6 a.m. time slot, then she made herself czar of the editorials after one of the DJs, Don Moniack, blasted her in an editorial. Lastly, she decided to ban certain albums from airplay. DJ resistance was so hostile that Villarreal-Price resigned in late July and White appointed Leigh Robartes as station manager until the Communications Board could meet again in the fall.

Robartes was a Moscow outsider who had recently moved to UI from Albany, New York where he had worked on a student radio station. He presented White with an alternative to Matt Kitterman, the other logical replacement to Villarreal-Price. Robartes had previous staff experience at Albany and could take charge of the perceived lack of discipline at KUOI. Robartes continued in the tradition of Greg Meyer and tried to integrate as many musical styles and tastes as possible in the KUOI format. He promised that hard rock and punk would not be played during business hours, two live call-in shows were initiated, the home womens Vandal games would be broadcast and Live from the Lobby would continue. The alternative format would be pursued and that competency would be facilitated through creativity. He continued the tradition of live coverage of UI events like the Jazz Festival, ASUI Productions, Lectures and the Renaissance Fair. Robartes weathered the storm of controversy and remained station manager until spring of 1989.

Robartes was replaced by Ken Fate, an old fraternity brother of Brad Cuddy, ASUI president. Fate had given up the fraternity but managed to get through improvements that past station managers had tried to obtain from the senate. His most noteworthy accomplishments were a remodel of the control room that put KUOI aesthetically in the upper leagues and the placement of Pacifica News in the KUOI daily format. KUOI had not had any national news since the beginning of the Reagan years. The half hour of Pacifica News as an award-winning program was a real credit to KUOI programming. Pacifica was so popular that NPR stations asked it to be broadcast at times when the NPR news wasnt playing. Fate was a good manager and was liked by all, but his style was perhaps too loose for the stations own good.

He turned the station over to Bent Anyan in May of 1990. Students being what students are, sometimes they get a little wild. In late July some students decided to drink beer in the KUOI studios. The janitors found empty beer cans and reported it to Dean Vettrus, the SUB manager. Vetrus warned Anyan to make sure that it didnt happen again, but it did. The result was that KUOI could only be opened during business hours until school opened again. Hal Godwin, vice president of Student Affairs, insisted that some new policy be instituted to prevent this problem (students drinking where they are not supposed to be) in the future.

He, ASUI President Dave Pena, and Anyan came to an agreement. They decided to resurrect the old Jay Shelledy plan that called for guidance from someone in electronic media. Anyan fired the DJs that caused the problem and opened up the DJ spots to a diverse group of students in the fall. He also questioned the action of Godwin. He said that the administration had violated the university rules and regulations by punishing the station for the action of individuals. Vetrus said that the Regents controlled the station and UI controlled the building. The Communications Board approved the Shelledy plan but did not appoint any advisers as of December 1990.

KUOI has has had to suffer incompetent station managers, hostile student governments, FCC regulations, budget cuts and interfering university officials. It has also been the source of inspiration and joy for both listeners and staff, whether it was broadcasting nearly inaudible static over the WWP lines or the high-fidelity stereo sound of compact discs. KUOI has launched dozens of careers for a wide and varied array of individuals. It has maintained a kind of continuity as if it were guided by some magical genetic DNA code. Whatever the challenge, the students could always get through one more year. Sue Miller, a DJ in the 1970s summed it up perfectly. After receiving her Masters Degree she decided to leave town immediately and left a note for the station manager because she wouldnt be doing her show that week. She also said, . . .KUOI is the only thing Ill really miss about Moscow.